Part 2 : Jimmy Sets Sail

/In spite of the many times I’ve shuffled his footprints, I only remember my grandfather, Jimmy, because he briefly lived in a turret. My Mum had done a good job on me. Together we’d turned the pages of Edmund Dulac’s exquisite picture books and I knew my stuff - mythical characters, sorcerers and little-folk resided in turrets.

I’d actually met my grandparents each year I’m told, but that year was different for a memory got laid. We’d arrived in Scotland after a very long drive and as I got out the car, grumbling and tired, Mum distracted me, calling, “Look!” and pointed up. A white handkerchief waved from a widow high in a turret and I was transfixed… agog. After a few brief and feverishly exciting moments scampering up a curving staircase, Mum embraced an elderly couple in tweedy clothes and all traces of heady alchemy disappeared. I was ushered into the turret – a sitting room where heavy drapes masked the curved walls and chintz sofas made it mundane. I was mute – crushed by the letdown. Dad chided me to be polite to the thin little man by his side. Jimmy had round glasses, big ears and a smiley face. A year later, after my grandparents had moved from the Cairngorm Hotel in Aviemore, he was dead. Following his footsteps supplements that imperfect memory.

You must agree that Edmund Dulac’s castle and The Cairngorm Hotel could look very similar to a five-year old. On the far right of the black & white photo is the turret where my grandparents stayed .

The two bottom Dulac illustrations are perhaps more of what I expected when I got to look inside the turret…

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

My maternal education didn’t end once I was past fairy tales. Much later, Mum confided that, as she’d once met a ghost, it was perfectly plausible that I too might encounter phantoms. Whatever the reason for their outing, she said, they had neither the means nor the desire to harm me. I should not be crass or scream, but rather remember my manners and behave as to any soul of greater substance. I haven’t ever had such a visceral encounter as Mum, but it was wonderful advice because when I do feel a dimension of the dead close by, I am comfortable with that. I suspect those are the buggers that lead me down rabbit holes whenever I sit down to write.

Mum was reserved, refined and well-read – not the sort you’d imagine given to dispensing advice on specters. She never spoke to me about sex, not once. Sex no, spooks yes. I appreciate my darling mother now more than ever, for such abnormal advice is hard to come by, whereas sex… well… I figured it out.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Back to Jimmy, Mum’s father. He was born in 1874 and while he grew up in leaps and bounds, so too did technology. The Suez Canal had opened in 1869 and shortly afterwards, a network of telegraph cables – above ground and below the sea – linked the globe. Telegraph poles often strode along in tandem beside the ever-increasing web of railway tracks. The construction of ships had finished changing from wood to iron in parallel with the switch from sail to steam.

The British Empire - on which so famously the sun never set - was at its height and there was no reason to doubt its longevity. Fundamentally the Empire was a global trading enterprise, though territories with little commercial merit were added to secure Britain’s sea route to India.

Rudyard Kipling, author of Just So Stories and Jungle Book, won the 1907 Nobel Prize for Literature. Kipling’s view and enthusiasm for Empire was shared by many a man and woman in the street. (Kipling doesn’t have such a good rap now with there being alternative views on Empire, but I think if his ghost is about, he’d probably have come a long way.)

The beautiful embossed cover of the first edition of The Jungle Book published in 1894 and a Just So Edition of 1902. We had a copy of this edition in the house when I was growing up.

Kipling actually has some marvellous quotes that have better stood the test of time and are worth looking up, but this one fitted better here.

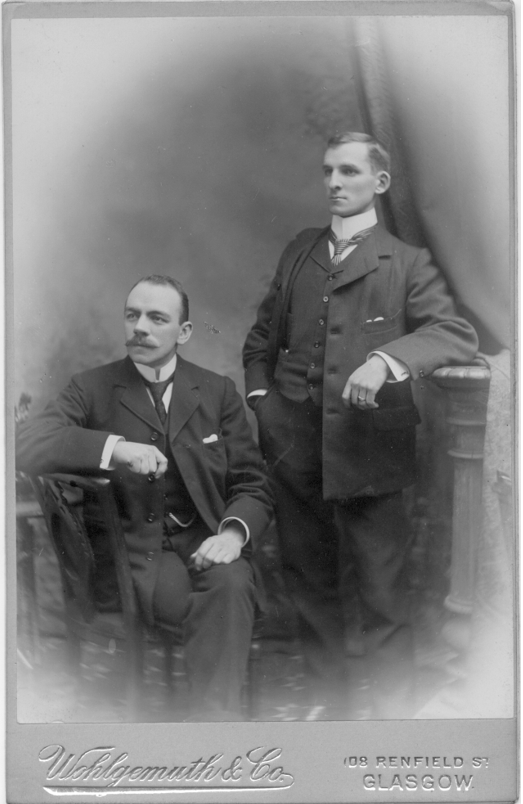

And it was in 1907 that Jimmy, a young man of 33, well-established with his own firm, property and community-standing is ready to roll. There is posterity on the Clyde.

There had been trouble with unions and strikers a few years before but they went back to work without much gain.

The shipyards thrived – a fifth of all ships in the world came to be built on the Clyde - and that meant orders down the line to suppliers like Jimmy’s firm, Steven and Struthers. The foundry prospered suppling propellers, stem and stern posts, foghorns and steam-whistles to name but some.

Glasgow was at the forefront of new technology: the Titan Clydebank, the largest cantilever crane in the world, had been commissioned at a local shipyard that year.

The Tiitan on Clydeside is 150 ft tall and was the world’s first electrically powered cantilever crane. The shipyards are gone but the crane is still there. It’s a tourist attraction now and brightly lit at night.

The photo of the Steven & Struthers brochure is one produced around 1910, after Jimmy returned from his overseas trip.

Yet the real new technology of the era was not mechanical - the world had gone wireless.

Credit for wireless telegraphy – radio - is laid at the feet of Marconi, an Irish-Italian inventor, physicist and entrepreneurial genius, born in 1874, the same year as Jimmy. Marconi, sent the first wireless message across the Atlantic Ocean in 1901. The scientists of the day said it was impossible due to the curvature of the earth – he proved them wrong.

The remarkable feat of plucking morse code signals out of the air, without the need for wires and cables, was little short of miraculous as was the speed with which Marconi developed applications - ship to ship and ship to shore communications were invaluable – and followed a few years later by Marconi’s nightly world news service to ships at sea.

Marconi at work and his famous Marconigrams. Ship to Shore radio meant shipping could be warned of storms at sea, The applications of wireless telegraphy for peace and war were endless and were the precursors to all our internet communications today.

At the time when Jimmy started his journey, taking the train from Glasgow, wrapped up against a Scottish winter, with a porter managing his cabin trunks and suitcases, radio was transforming trade and finance, enabling transactions in ‘real time’. A ship’s newspaper compiled from Marconigrams sent by wireless the night before, would be ready to read with his breakfast on the high seas. At almost every port he’d be met by British administrators, agents and professionals. He would buy pictorial post-cards to send home – the Edwardian text-message – and his card would join many millions of others in postbags world wide. And he’d carry a camera to record his own images – probably the Brownie, the world’s first mass-produced camera. He’d be able to buy film at most ports at shops stocked with British goods, for each stop was already catering to the Empire’s well-heeled ocean-liner travellers.

Jimmy might well have felt pride and confidence in the accomplishments and achievements he saw around him. I am not suggesting my grandfather had a sense of arrogance or entitlement, for he was well known to be a mild and unassuming man. He’d have been well grounded by his father, John Steven, who had come up through the ranks of apprenticeship to build his own innovative and successful foundry business. According to a contemporary business article, John still used the dialect of the Gorbals and, had a “frank liking for his men”. A paragraph added that Steven and Struthers provided working conditions, “far above both the requirements of the law and trade union regulations”.*

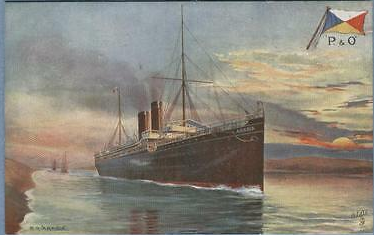

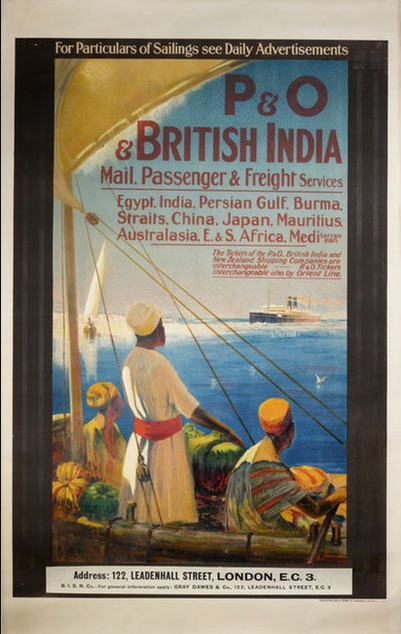

P&O’s ss Arabia was the ship that my grandfather, Jimmy, boarded at Tilbury docks on 16 November 1907.

It’s a cold, dull day when Jimmy steps onto the gang-plank of his P&O ocean liner, the SS Arabia, at Tilbury docks on the Thames. It is Saturday 16 November 1907. Like clockwork, each Saturday a P&O liner left Tilbury for India. Some seaman on board may perhaps have remembered when sailing times shifted – sometimes for days – dependent on the vagrancies of British weather.

When I started to explore what it must have been like on board the SS Arabia, my heart flipped for as travel by ocean liner had become commonplace, the demand encouraged competition – and publicity campaigns directed at the discerning passenger featured the elegance of the interiors. Décor – art – ambiance!

*Extract from ‘Captains of Industry’ by William S Murphy 1901 https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/John_Steven

I’m reading Marconi: the Man Who Networked the World by Marc Raboy, 2016 Oxford University Press and loving it!

![20190831_091833[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5600d12ae4b088bb5b7e347e/1567608079196-7ELNNFAOU9NIARLD2K9Z/20190831_091833%5B1%5D.jpg)